Proof of Work BTC vs. Proof of Stake ETH Security Models

Responding to Hal Press of North Rock Digital

(Note: this post gets into the weeds of Proof of Work vs. Proof of Stake blockchain security models and talks through specific scenarios and attack vectors. That said, I tried to define key terms and make the post as accessible as possible for all readers. For a higher level discussion of PoW vs. PoS security features and flaws, or as primer for this post, I encourage you to first read my previous post: Why Decentralized Money Matters.)

On April 19th, Hal Press of North Rock Digital published a Medium post titled “Decentralized SoV — PoS vs PoW”.

I respect Hal as a thinker and investor in the space and have had friendly conversations with him in the past. In particular I respect his willingness to make his thoughts and ideas public, solicit feedback, and change his mind when warranted. I always eagerly read his work when he publishes it.

His post argues for the characteristics of Proof-of-Stake (PoS) being superior to Proof-of-Work (PoW) as it relates to being a store-of-value (SoV). On Twitter, Hal asked to hear from both people who agree as well as disagree with his arguments. I disagree with the overall thesis and conclusion, and below is my attempt to respond to his arguments one by one and change his mind.

Since the conversation is really one of ETH (PoS) vs. BTC (PoW), I will refer specifically to ETH and BTC below so as to be able to provide specific empirical examples.

Economic Cost to 51% Attack: PoW vs. PoS

Before we dive in, I think it’s helpful to define what a 51% attack actually is. I’m no blockchain software program expert but I’ll do my best.

A blockchain is just a decentralized ledger, and gets its name because it’s literally a chain of blocks, where a block is a batch of new transactions updating the state of the ledger. To add new blocks to the chain, you need to bring resources to bear in the form of energy (specifically, hashrate) for PoW Bitcoin or “stake” (specifically, ETH) for PoS Ethereum. If you control >50% of the resources adding new blocks to the chain, you can conspire to build a longer, dishonest blockchain in private faster than the rest of the network can build an honest blockchain. On this dishonest blockchain you can reverse recent transactions or double spend tokens. Think of it as counterfeiting. You could also execute a Denial-of-Service attack by not including specific transactions in your blocks.

Nodes are locally run software programs that verify the blockchain based on consensus rules that they all agree upon. One of those rules is to accept the longest blockchain as the true blockchain, because it has performed the most “work” to add blocks to the chain. Hence, “Proof of Work.”

So, once you’ve built your longer, dishonest blockchain in private you can broadcast that blockchain out to the rest of the network, and nodes will pick up your blockchain and agree that is the true blockchain because it has the most blocks, and confirm it. In order to keep proposing dishonest blocks, a 51% attacker must maintain >51% of the resources dedicated to processing new blocks. The term for proposing new blocks on PoW is “mining,” and on PoS it’s “validating.”

The post begins by contemplating the theoretical dollar costs of securing each network vs. attacking it and starts with PoW:

We believe PoS is a fundamentally more secure system for a variety of reasons. Firstly, each unit of security costs less with PoS. To understand why PoS provides more efficient security than PoW we first need to explore how these consensus mechanisms generate security in the first place. A consensus mechanism is as secure as the cost to 51% attack it. The efficiency of the system can then be measured by the cost (issuance) required to generate a unit amount of security. In other words, how many dollars the network has to pay out to receive $1 of protection from a 51% attack. For PoW, the cost of a 51% attack is primarily the hardware required to obtain 51% of the hashrate. The relevant metric is how much money miners require to invest $1 in mining hardware. The math tends to work out close to 1 to 1 meaning miners require 100% annual rate of return on their investment or in other words $1 of annual issuance for each $1 they spend on hardware and utilities. In this context, the network needs to issue roughly $1 of supply each year to generate $1 of security.

I believe "rate of return" is misused here. When you earn $1 on $1 of costs, your rate of return is 0%, not 100%. I agree that miners are incentivized to add hashrate to the Bitcoin network so long as they have a positive expected return in doing so. As has been written by Nic Carter et al, the very fact that miner margins are slim at equilibrium is a consequence of PoW being a perfectly competitive free market competition to receive newly issued tokens and fees, which establishes fairness and credibility.

What is actually important in evaluating the security of BTC vs. ETH is this: PoW security is unbounded and positive-sum — the hashpower I bring to bear has no consequence on the hashpower you bring to bear. PoS security is bounded and zero-sum — my stake necessarily takes away from your stake. I will circle all the way back around to this at the end, so keep this idea in mind throughout.

The post continues by exmaining these same dynamics for PoS:

In the case of PoS, stakers are not required to purchase hardware, so the question becomes what return do stakers demand to lock up their stake in the PoS consensus mechanism. In general, stakers require a significantly lower rate of return than the 100% miners typically demand. The primary reason for this is that there is no incremental cost outlay and their assets do not depreciate (mining hardware typically depreciates close to 0 after a few years). The required rate should generally fall in the 3–10% range. The current ETH staking rate of ~5% falls right in the middle of this range. This means that to gain $1 of security a PoS needs to issue $0.03-$0.10 of issuance. This is 10x-33x more efficient than PoW (20x more in the case of Ethereum’s PoS). To conclude, this means that a PoS network can issue ~1/20th the issuance of a PoW network and be just as secure. In the case of ETH, the transition to PoS allowed the protocol to issue about 1/10th the issuance and be twice as secure as it was during PoW.

I respectfully disagree. One cannot say a certain PoS consensus mechanism is x% as secure or efficient as Bitcoin's PoW because comparing PoS to PoW is comparing apples to oranges. They are fundamentally different and accomplish different things. PoS does not, for example, provide a way to achieve decentralized and fair distribution of a digital asset as PoW does, and decentralized and fair distribution is paramount to establishing and maintaining credible neutrality. Credible neutrality, by Hal's own admission, in turn, is a "critically important charactersitic" of a SoV. There is more on the topic of credible neutrality below.

Beyond this, security is only considered in terms of dollar cost to attack, not in terms of energy cost to attack. This assumes money is freely and always convertible to energy at a fixed rate, which is not a valid assumption. If I have all the money in the world but do not have an adequate energy source or competitive mining equipment, I cannot attack the Bitcoin network. With enough money I can perhaps marshal the resources to mount an attack on the network, but there is no getting around the need for the application of actual physical watts in order to do so.

The argument is one of dollar costs needed to achieve a level of dollar security, but bitcoin isn’t secured by dollars, it’s secured by energy.

Energy is the currency of the universe. It cannot be faked or exploited like logic can.

One of the profound inventions of PoW Bitcoin was importing physical security properties to the digital world.

Ability to Withstand a Downward Price Spiral

The next section argues for the security characteristics of each chain in the event of a price spiral, starting with PoS:

This efficiency is not the only advantage. Both consensus mechanisms share a common issue, which is that the security of the chain is correlated to the price of the token. This has the potential to create a self-reinforcing negative feedback loop whereby the reduction in token price causes a reduction in security, which therefore causes a decrease in confidence and drives a further decrease in token price and then repeats. PoS has natural defense against this dynamic, PoW doesn’t. The attack vector for PoS is much more secure than PoW. To attack a PoS system you must control a majority of the stake. To do this you must purchase at least as many tokens as are staked from the market. However, not all tokens are available for sale. In fact, much of the supply is never traded and is effectively illiquid. Furthermore, and most importantly, with each token acquired the next token becomes harder and more expensive to acquire. In the case of Ethereum, only ~1/3 of tokens is liquid (moved in the last 90 days). This means that once a steady state staking participation rate of closer to 30% has been reached it will be extremely difficult no matter the amount of money possessed, to attack the network. An attacker would need to purchase the entire liquid supply, which is impractical and nearly impossible. Another important feature of this defense mechanism is that it is relatively unaffected by price. Because the limiting factor to attack is liquid supply rather than money it does not get much easier to attack the network with lower prices. If there is not enough liquid supply (measured as a % of total tokens) to purchase, it doesn’t matter how cheap each token becomes because the limiting factor is not price. This price insensitive defense mechanism is incredibly important to deter the potential negative feedback loop that declining price could otherwise create.

It is my interpretation that this and the following paragraph contemplate each network’s ability to withstand an acute, targeted price attack on the network’s native token from a security perspective. I say this because, in the alternative scenario where the token price just gradually bleeds out toward zero, the token has already failed as a store-of-value for other reasons and I agree with Hal that the network’s security would dwindle alongside the value of the network.

While “the security of the chain is correlated to the price of the token” in absolute terms, what actually matters for security is not the absolute cost to attack but rather the Benefit-to-Cost Ratio of Attack. A low absolute security budget can serve as ample security for a system that nobody wishes to attack, and a high absolute security budget can be insufficient if the benefit to attacking the system is even greater.

To summarize, this section argues that Ethereum’s security is insulated from a scenario in which the ETH token price falls dramatically because what matters for attacking the network is not the theoretical dollar cost to do so (as is argued in the previous paragraph) but rather the ability to secure a majority of the stake. I agree with this but will mention here that 1) this dynamic applies for all price environments, including a dramatic price spike, and 2) the corollary for Bitcoin is that what matters for attacking the network is the ability to amass a majority of the hashpower, not the theoretical cost to do so.

The argument further assumes ~1/3 of the ETH supply is staked, ~1/3 is liquid and ~1/3 is illiquid, meaning all of the liquid supply would need to be acquired to 51% attack the network. “Illiquid” is defined rather loosely to be not moved in the last 90 days (I myself consider my entire stack of ETH to be liquid and having not moved in the last 90 days), but that’s not really important.

What’s important is the argument rests on the assumption that liquid vs. illiquid supply is a constant, which I believe is a faulty assumption. I don’t see any reason to be certain currently illiquid supply will remain illiquid at any price and under any circumstance. In fact, I think an argument can be made that in the event of a sudden crash in the price of ETH, a larger proportion of the supply would become “illiquid” as holders become less inclined to sell at lower prices. The flipside of this logic is that in a sudden dramatic spike in the price of ETH, some previous illiquid portion of the supply might become liquid, induced to sell at higher prices.

I’ll grant an edge case of there being a coordinated group of price insensitive holders who’s primary motivation is to maintain control over the network. Of course, if that is the case, the network is already captured and is thus not fit for purpose as money because it is not credibly neutral. This does not mean it cannot function as a SoV or be an appreciating and/or productive asset, much like an equity security.

The post continues with a brief discussion of PoW security in a price spiral:

In the case of PoW, in addition to being 20x less efficient, there is no such defense mechanism. Each hardware unit may be marginally harder to acquire than the next, but there is no direct relationship and if there is a correlation that does exist it is weak at best. Importantly, it also becomes significantly easier to attack at lower prices as the number of hardware units required decreases linearly with price and the supply of hardware units does not change. It is not reflexive in the manner the PoS liquid supply defense is.

A few things to mention here in response.

First, I believe there is indeed a direct relationship, or correlation, between how hard it is to acquire the nth bitcoin mining hardware unit and how hard it is to acquire the nth+1.

Second, the number of hardware units (i.e. hashpower) required to 51% attack the network does not decrease linearly with price, but rather with total network hashpower, which over the long-run can be expected to be a function of price.

Third, what the author describes here is a reflexive process, where security influences price and price influences security, whereas above it is argued that it is Ethereum’s security which is not actually reflexive with price.

In any event, it’s worth contemplating what might happen in the event of an acute, targeted attack on the price of BTC. I believe miners would be incentivized on the margin to power down and take their most expensive hashpower off the network until their revenues covered their costs. This would reduce total hashrate securing the network and thus reduce the hashrate needed to 51% attack the network. A successful 51% attack might render the network worthless and thus an attacker could expect to profit in fiat terms from having a large short position on BTC before launching a successful 51% attack.

Practically and empirically though I think there are three problems with this theory.

First, it would take the amassing of a large, unknown quantity of hashpower in the dark to prepare to launch a 51% attack. I say unknown because, as per the theory of miners bringing hashrate on-and-off-line in response to price, we do not know the amount of idle hashpower that could be brought online to defend the network against a 51% attack.

Amassing this large, unknown quantity of haspower in the dark could in theory be done for any BTC price level, but the lower the BTC price, the less hashpower we’d expect is committed to mining BTC, so we might expect this to be easier the lower the BTC price is.

Second, it would take a large, unknown quantity of capital to influence the price of BTC long enough to change miner behavior. Miners aren’t practically going to respond to price volatility by flipping on and off hashpower overnight; in reality it’s more of a slow-moving process. Moreover, miners might actually bring hashrate online if they suspect a 51% attack is underway.

Take the above two points together and what you get is a huge, sunk physical and/or economic cost if you’re unsuccessful and thus the risk in attempting to execute a 51% attack is astronomical.

Third, this possibility and seemingly the same economic incentive has existed for 14 years and yet, thus far, nobody has executed a successful 51% attack on Bitcoin or even gotten close enough that we know it was attempted. Why not? Probably because it is easier said than done, and the Benefit-to-Cost Ratio of Attack has never been high enough to induce an attack on the network. What we know for certain is that, to date, the Bitcoin security model has been successful in imposing prohibitive physical costs on would be attackers.

Bringing it back up, with respect to price-induced network attacks, I think there is one key insight to consider with respect to Ethereum PoS security vs. Bitcoin PoW security.

It is the actual acquisition of the token that matters for 51% attacking Ethereum, and token ownership is bounded and zero-sum, whereas it is the application of physical watts that matters for attacking Bitcoin, and energy is unbounded and positive-sum. The actual ownership of the token has no direct consequence for 51% attacking Bitcoin.

I think the implication of this is that ETH security may actually be more susceptible to a dramatic price spike, as opposed to a price crash, because exisiting holders of ETH will be more willing to part with their ETH at a higher price. An attacker who wishes to gain control of the network can keep bidding up the price of ETH until they are able to acquire 51%, using other stakeholder’s own economic incentives against them, and once the attacker gains 51% control of the network nobody can do anything to regain control without the cooperation of the attacker.

In contrast, BTC security is enhanced by a dramatic price spike because it incentivizes miners to bring more watts to bear to earn BTC new issuance and network fees.

In PoW economic incentives are aligned with security. In PoS, they are not necessarily.

Does PoS Naturally Drive Centralization Over Time?

The post continues by contemplating whether PoS naturally drives centralization:

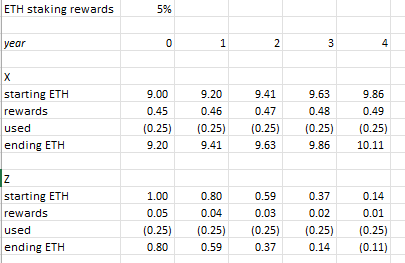

Another misconception about PoS is that it drives centralization by rewarding large stakers more than small stakers. We believe this to be incorrect. While, large stakers receive more staking rewards than smaller stakers, this does not drive centralization. Centralization is the process by which large stake holders increase their percentage of the stake over time. This is not what occurs in the PoS system. As large stakers have a larger stake to begin with the larger rewards do not increase their percentage of the pool. For example, if 10 ETH is staked between two counterparties. Counterparty X has 9 ETH and counterparty Z has 1 ETH. X controls 90% of the stake. A year later X will have received 0.45 ETH and Z will have received .05 ETH. X has received 9 times the amount of rewards as Z. However, X still controls 90% of the stake and Z still controls 10%. The proportions have not been altered and therefore no centralization has occurred.

This argument assumes no party will ever use their ETH, meaning sell (trade for another monetary good) or redeem (pay) for goods and services, including as for gas on the Ethereum network. If no party ever used their ETH, then ETH would necessarily have no value. So in evaluating whether PoS drives network centralization we must assume that certain parties in the ecosystem will use their ETH.

In this case, consider the quoted example of parties X and Z who have 9 ETH and 1 ETH, respectively. Say each of them have the same basic needs (food, shelter, gas) and wish to use their ETH to meet these needs, and these needs are met by using Y ETH per year. Y could be any positive number and the network becomes more centralized over time. For example, we could assume Y = 0.25 ETH.

Party X gains a larger and larger control of the supply over time and is not required to do any work (supply any energy) to do so.

Again, while I stress the ownership of BTC has no direct implications for Bitcoin security like it does for ETH, I think it’s worth examining concentration of ownership dynamics anyways.

Bitcoin does not suffer from the same fate of increased concentration of ownership over time because in order to earn BTC you must contribute “work” exogenous to the value of the BTC token, either in the form of supplying hashpower to earn newly issued BTC and fees or in the form of providing goods and services that are of value in an economy in exchange for BTC. There is no interest rate or staking reward to be earned merely by acquiring and staking the native token. Because the supply of BTC is limited and finite, there will be fierce competition to earn and save BTC, which naturally decentralizes the supply of BTC over time.

This is being demonstrated empirically through the number of BTC addresses with small balances increasing steadily over time as more and more people stack their first sats and accumulate, while the number of BTC addresses with large balances has been declining since 2017 as BTC gets distributed after an initial adoption phase (2009-2017) where addresses of all balances were necessarily increasing off a base of zero.

This isn’t to say that there can’t or won’t also be fierce competition to earn and save ETH. The difference is there will exist a way, via staking, to grow one’s ETH holdings without contributing any work to the Ethereum economy and no such opportunity will exist for BTC. You can argue that providing stake is contributing to ETH’s security budget, which it is, but the value of this contribution is endogenous to the Ethereum network, is dependent on the ETH token price and doesn’t have any tie to the physical world like the application of physical watts does. No physical input is required to “earn” ETH, whereas it is required to earn BTC.

In this way, PoS and ETH echoe characteristics of fiat and/or equity, and PoW and Bitcoin echoe characteristics of gold. And while clearly both can exist and compete for a period of time, only one has withstood the test of time for thousands of years.

There is no interest rate or staking reward on gold — you have to go into the ground and get it.

To be fair, the supply of ETH is also, empirically, being distributed over time in similar way to BTC, although some characteristics of ETH such as the pre-mine and an evolving and (thus far) unpredictable issuance schedule are indicated in some of the uneveness in distribution over time in the second chart below.

ETH may very well become more decentralized over time; I see no reason that couldn’t be the case, and thus far that has been the case, but remember thus far it has also been the case that ETH was secured by PoW. It remains to be seen what happens now that ETH has transitioned to PoS.

What I believe is clear is that the staking reward in a PoS system is a naturally centralizing force for reasons laid out, which will battle the natural decentralizing force of the distribution of an economic good which has undergone a monetization event.

Fee Security and Tail Emissions

The post continues with a discussion of the oft-debated BTC fee security model and potential tail emissions:

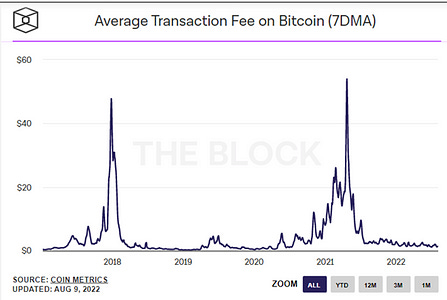

What happens when Bitcoin halves its issuance every four years? The system fundamentally becomes 50% less secure assuming all other variables are held constant. Historically, this has not been a large problem as the value of the issuance (and therefore the security) is a function of two variables. The number of tokens issued and the value of each token. As the price of the tokens has more than doubled around every halving cycle, this has more than compensated for the issuance reduction on an absolute basis. The absolute security of the network has increased through each cycle despite the number of tokens being issued halving. However, this is not a sustainable dynamic long term for multiple reasons. Firstly, it is not realistic to expect the value of each token to continue to more than double with each cycle. Exponential price increase is mathematically impossible to sustain over long periods of time. To illustrate this point, if BTC price doubled every halving cycle it would exceed global M2 after ~7 more halving cycles. Eventually, BTC price will stop increasing at this rate; when it does, each halving cycle will drastically cut into its security. If the BTC price declines around each halving cycle the security reduction will be even more significant and could trigger the negative feedback loop referred to earlier. This security system is fundamentally unsustainable so long as prices are capped, which they are. The only way to counter this issue is to generate meaningful fee revenue. This fee revenue could then replace some of the issuance and continue providing an incentive for miners and therefore provide security even after issuance is reduced. The issue for Bitcoin is that fee revenue has been negligible, and also declining, over a long period of time.

In our opinion, the only practical way to generate security over the long term is through significant fee revenue. Therefore, to function as sustainable SoV a system must generate fees. The alternative is tail emissions, which guarantees inflation compromising the SoV utility.

If I could summarize, the basic argument here is that Bitcoin doesn’t generate enough fees to incentivize miners to contribute network-securing hashpower to earn those fees, and instead it relies on the block subsidy which halves every four years and will ultimately go to zero.

The first thing to say in response to this argument is that so far, BTC’s security has worked, and it cannot be proved it won’t work until it does indeed fail. I say this because many bitcoin critics speak as if the security model has aleady failed, or is intractably doomed to fail once the block subsidy goes away. This is unequivocally incorrect. Nonetheless, contemplating how the future might unfold is definitely valuable.

The second is that this argument always assumes a static fee market. Instead, the fee market should be assumed to be a changing and emergent phenomenon, like Bitcoin itself. We’ve already seen periods of dramatic fee spikes during adoption waves in Bitcoin’s limited history, which drive scaling solutions, which lower fees until the next adoption wave, as the quoted graph above illustrates. In fact, we’ve just recently undergone another emergent, fee increasing event with the launch of ordinals.

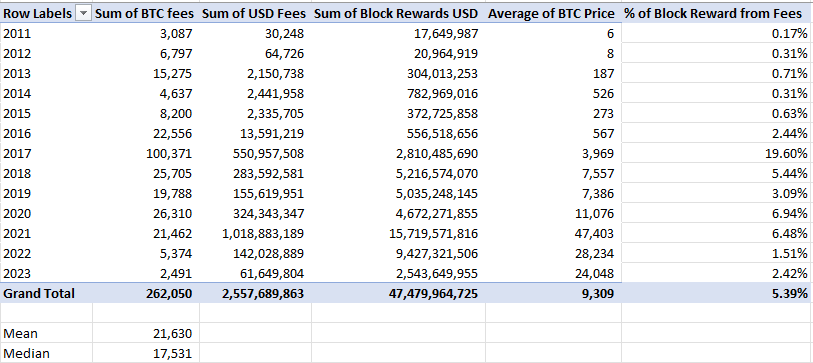

To say that Bitcoin fee revenue has been neglible or decreasing over time, however, is simply inaccurate. The below table is generated from Glassnode data and begins in 2011, which is the first year for which Glassnode has consistent data.

What you can see is that, subject to cyclical adoption waves, the overall sum of block rewards (fees + block subsidy) has been increasing in USD terms, and the percentage of the block reward coming from fees has been increasing just as one would expect with the block subsidy halving roughly every four years, peaking at ~20% during the 2017 bull market.

2023 of course only includes ~3.5 months of data, I included it just to show the apparent inflection point in fees as a % of block rewards as the market has turned and ordinals have burst onto the scene in Q1. The measures of mean and median fees in BTC terms only include 2011-2012.

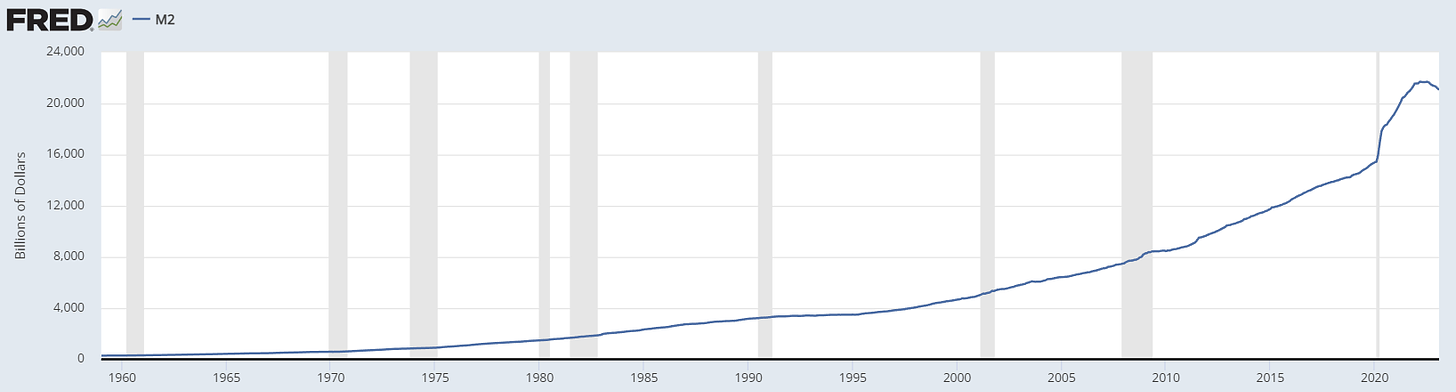

To be fair, Hal argues that so far the halving events have not been a problem for Bitcoin security because price has been increasing fast enough to more than offset the halving of the block subsidies. He goes on to say though that this can’t go on forever, which is true, and to illustrate the point argues the market cap of BTC would exceed global M2 after doubling for seven more halving cycles.

I think just five doublings off of $30k gets you to a market cap roughly equivalent to today’s global M2 of $21 trillion, but 1) I’m not sure M2 is the right metric to compare Bitcoin’s monetization potential to (topic for another day) and 2) this assumes no growth in M2 for the next 20 years.

The last couple months notwithstanding, global M2 has been increasing steadily at 7% per year since 1959, since 1970 (year before leaving the gold standard), and since 2007 (year before GFC). If it continues to grow at 7% through 2044, it will be $95 trillion.

The point is that when you factor in the expected debasement of the denominator, there is room for more doublings than you might expect, and certainly room for enough to carry bitcoin through to the stage where the block subsidy is neglible compared to the fee market.

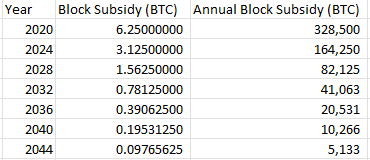

Fees will continue increasing as a percentage of the block reward, and miner revenue from fees should surpass miner revenue from the block subsidy sometime in the next 10-20 years (likely between the 2036 and 2044 halvings).

Average annual BTC-denominated fees over the 12 year history for which Glassnode has consistent data (2011-2022) is 21,630 and the median is 17,531 as shown above, with year by year figures volatile as the fee market is punctuated by adoption cycles. As a thought exercise, if we assume this stays constant and average annual BTC fees are ~20k going forward, then fees roughly equal the block subsidy in 2036 and exceed it in 2040.

It should be apparent, then, that the BTC price will not need to keep doubling every four years forever to maintain Bitcoin’s existing security budget. That would only be true in the absence of a fee market.

If we expand the table to show a theoretical progression of Bitcoin’s security budget under some assumptions, it shows the reality of the situation much more clearly.

The below table assumes the BTC price continues doubling every four years off a base of $30k in 2024 until hitting $960k in 2044, which would give it a market cap of $20 trillion, putting it on par with gold if we assume gold’s market cap compounds 3% per annum from today’s $13 trillion. After 2044, I assume the BTC price compounds 3% per annum, in-line with what many I think would say is a reasonable forecast of global GDP growth.

I further, conservatively assume annual fees remain 20k BTC per year, even though in a world where BTC keeps doubling in price every 4 years for the next 20 years we might expect the increased global adoption and demand for scarce bitcoin blockspace to have driven fees higher as it has in previous adoption waves.

Under these assumptions, BTC’s security budget increases in USD terms on average every year as increasing price more than offsets a decreasing block subsidy until the block subsidy is neglible as compared to fees. This is exactly how bitcoin was designed.

Yes, the security model depends on continued adoption and monetization. It always explicitly has. Cost to attack rises and falls reflexively with benefit to attack.

Again, these are just illustrative assumptions meant to refute the notion that bitcoin will never generate enough fees to secure it long-term. In reality the course of events will likely deviate from this table in some signficant ways. My bet is that if we’re still talking about Bitcoin in 2044, the annual fee market for Bitcoin blockspace will greatly exceed the 20k BTC it has average over the past 12 years and the steady-state annual security budget at maturity will exceed 0.10% of network value as displayed in the table.

I recommend this and this for more detailed discussions of Bitcoin’s security model and potential 51% attack vectors.

Long-Term Security and Credible Neutrality

Long-term security represents the most important property of an SoV. For example, gold has captured the majority of the SoV market for so long as nearly all market participants are confident that it will remain legitimate long into the future. For a crypto asset to become an adopted and successful SoV, it too must convince the market that it is extremely secure, and that its legitimacy is guaranteed. This can only be possible if the protocol’s security budget is sustainable for the long term, inherently favoring a PoS system that has a large and durable fee pool. We believe the most likely candidate for this system is ETH. It is one of only two L1’s with a significant fee pool. The other, BNB, is extremely centralized.

I agree that long-term security, or what I would more broadly call durability, is one of many important properties to consider when evaluating a free market economic good’s suitability as a SoV, or more broadly money, in addition to scarcity, verifiability, portability, divisibility, and fungibility. Gold has held the role of the superior SoV, and money, for most of human history (since the invention of finance) due to its unmatched scarcity, durability and verifiability. Fiat was invented to paper over (pun intended) gold’s shortcomings on portability and divisibility .

In my view, Bitcoin has superseded gold and is the first absolutely scarce monetary good, while also solving for the problems of divisability and portability. It is absolutely scarce because its fixed supply is verifiable and credible. I cover in this post why I think the PoW security model is not only durable, but is purpose-built to keep Bitcoin decentralized and thus censorship-resistant and credibly neutral. I believe it is the only sufficiently decentralized, absolutely scarce, and credibly neutral cryptoasset in the market today. Moreover, monetary networks converge on a single medium over time, because nobody wants to hold the second best money once it becomes common knowledge what the best money is. See: silver vs. gold, last 2,570 years.

I agree with Hal that a sufficiently large and sustainable fee pool is one key aspect to a cryptoasset’s security, but that alone is not enough to guarantee security. While a cryptoasset being adopted as global money guarantees a large and sustainable fee pool, a large and sustainable fee pool does not guarantee a cryptoasset will be adopted as money.

Scarcity enforced through decentralization and credible neutrality is another key aspect, and this is where I believe Ethereum falls short.

Credible neutrality is the second critically important characteristic of a successful SoV. Gold has no allegiance or reliance on anything. This independency creates its success as an SoV. For another asset to be widely adopted as an SoV it must also be credibly neutral. For a cryptocurrency, credible neutrality is accomplished through decentralization. Today, the most decentralized cryptocurrency is undoubtedly Bitcoin. This is primarily because Bitcoin has very little development effort, and the protocol is mainly ossified, but nonetheless the fact remains that it is by far the most decentralized protocol today.

Credible neutrality is, in my view, why ETH will never match BTC as money.

ETH was pre-mined, meaning that its supply was allocated to a privileged few at the control of the founding team. This is in contrast to Bitcoin, which executed a “fair launch.” A fair launch is when every market participant can permissionlessly earn tokens on the same terms as every one else, which to my mind is only executable via a PoW mining distribution mechanism (which, mind you, Ethereum did deploy up until the merge in order to decentralize the network!).

If you were to create a new asset and wanted it to be distributed globally in the fairest way possible, I don’t know how you could do better than PoW Bitcoin. This has huge downstream implications for the asset’s credible neutrality and, thus, ultimate suitability and adoption as money.

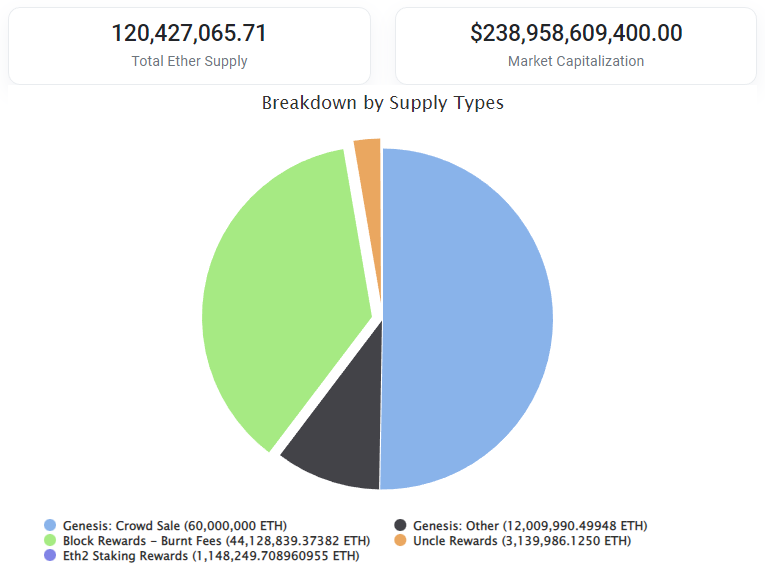

Here’s what this shows you. Of the current 120 million circulating supply of ETH, 72 million were granted or sold to founders, principal investors, etc. (“Genesis: Crowd Sale” and “Genesis: Other”). 47 million were earned fairly through PoW mining (“Block Rewards minus Burnt Fees”, and “Uncle Rewards”). And 1 million have been earned through Eth2 Staking Rewards. Going forward, of course, staking rewards will be the only way to earn new ETH supply, and the green piece of the pie, the piece that was earned faily, will shrink as more fees are burned.

So ETH is an asset where 60% of the supply was handed out to founders and early investors, and then within about six years these same people decided to change the rules of the network so that the only way to earn ETH new issuance on a go-forward basis is to have a pre-existing stack of ETH which can be staked.

The consequences of ETH’s pre-mine have been predictable: when push comes to shove, Ethereum is controlled by a select group of founders and paid core developers.

Ethereum lost all credible neutrality when it hard-forked to reverse transactions that stole ETH from the Ethereum DAO through a code exploit in 2016, a year after Ethereum’s founding in 2015. If the pre-mine was Ethereum’s original sin, this was blasphemy.

I’m no expert on the event and probably need to read a book or two on it, but I think I can confidently say when a consortium can effectively vote themselves back the stolen money, the money is not credibly neutral. Whether or not Ethereum has sufficiently decentralized so this could not occur again today is up for debate.

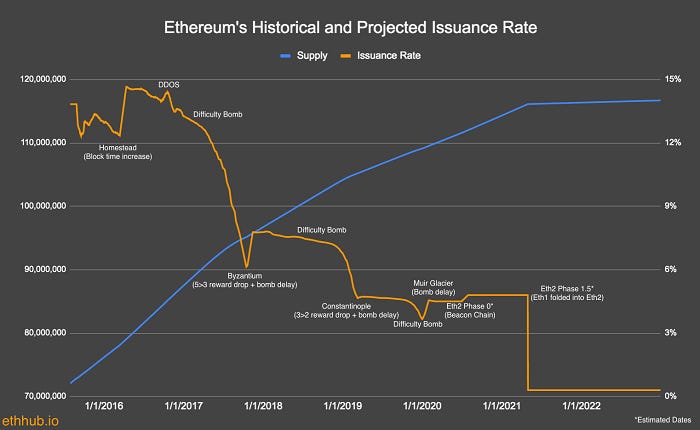

Beyond that, Ethereum has had a constantly changing monetary policy throughout it’s short life. Its latest incarnation, EIP-1559, was implemented in August 2021 and introduced both a deflationary element, the burning of fees, and an inflationary element, new issuance for validators (i.e. stakers). I actually think EIP-1559 is the best monetary policy Ethereum has adopted yet and is likely to help accrue value to the ETH token, but who is to say it will not change again as it has so many times in the past?

Can It Be Banned? Is It Decentralized?

If you tried to kill Bitcoin today, it would be extremely hard. If you tried to kill ETH today, it would still be extremely hard, but likely easier than BTC.

However, we believe it is more important to look at the end state than the current state so long as there is a realistic path to achieve this end-state. Ethereum has a clear roadmap ahead of it. We believe that while we are currently only in the middle of this roadmap, eventually (I’d estimate ~8–12 years) this roadmap will be complete, and the significance of the core developer team will fade. At this point ETH will have a compelling case that it is more decentralized than BTC in addition to possessing far superior long-term security.

If you wanted to kill Bitcoin today, it would be nothing short of shutting down the global internet.

If you wanted to kill Ethereum today, there are multiple known attack surfaces with unknown levels of vulnerability.

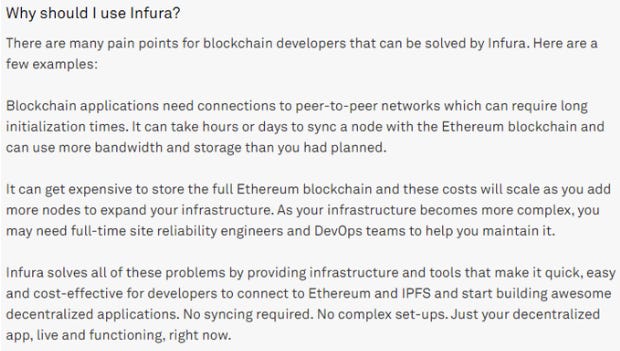

It is possible you would simply have to call up Infura, a large, centralized 3rd-party Ethereum node operator, and order them to shut down.

Exact usage stats aren’t public, to my knowledge, but Infura is said to “underpin the majority of decentralized applications in the Ethereum ecosystem.”

Infura is run by ConsenSys, an ethereum development studio founded by Jospeh Lubin, which is also responsible for the development of MetaMask. Lubin was likely was one of the aforementioned principal investors in the Ethereum pre-mine, and as Ethereum’s COO was also likely alotted a large portion of the ~6 million ETH alotted to “early project contributors.”

It was estimated at one point that that Lubin controlled 5-10% of the circulating supply of ETH, although he has said publicly that his holdings have “never been even close to even half of a percent.”

From Infura’s website:

As described, running an Ethereum full-node is costly, complex and time intensive to set-up. Luckily, one of the people that made it so has set up a company that will do it for you!

This is in contrast to Bitcoin, where running a full-node takes up very little storage space and can be done by anyone with a standard laptop costing ~$200. Moreover, the sacredness of the ease and accessibility of running of a bitcoin full-node was at stake and upheld in the 2017 blocksize wars, with the network prizing decentralization above all else and promoting its long-term credibility.

Vitalik Buterin has been asked about Ethereum’s reliance on Infura multiple times (credit Lyn Alden for prividing these links). His basic response has been (paraphrasing) “If Infura died tomorrow, Ethereum applications would definitely get significantly harder to use, though at the same time it is possible to use Ethereum applications without relying on Infura.”

Indeed, in November 2020, Infura went down and many exchanges had to stop allowing Ethereum chain withdrawals.

Infura runs completely on AWS, opening up another centralized attack vector on the Ethereum network. “Hey, Jassy, turn off Infura’s cloud or go to jail.”

And finally, with a combined market cap of $113 billion vs. ETH’s market cap of $218 billion, the two largest ETH-supported stablecoins, USDT and USDC, obviously hold enormous sway over support for any future forks.

Bringing it back up, all this is to say that I don’t believe Ethereum is, or has a visible path to being, sufficiently decentralized so as to be credibly neutral. I’ll grant this is a subjective, individual matter of opinion, and I have stated my case. It has, in its brief history and on multiple occasions, changed the rules, consensus mechanism, and monetary policy of the network in ways that favor pre-existing token holders, and made design choices that explicitly open the network up to capture and centralized attack vectors.

This isn’t to say that Ethereum can’t sufficiently decentralize further in the future to eliminate all these attack surfaces, or even that this is necessarily a bad thing for the Ethereum platform or ETH token value accrual! We just need to recognize what ETH is and is not. I view it as more like equity in a platform which provides services and collects fees, like AMZN stock/AWS or AAPL stock/app store. It is not credibly neutral, absolutely scarce decentralized money, nor is it even trying to be. There is no current cap to the supply of ETH. ETH is trying to be both a utility token, used as an oil-like commodity for running decentralized applications, and a monetary asset, used as a bond-like investment to earn yield through staking and as collateral for borrowing in DeFi.

So far, with the 2nd largest market cap among cryptoassets behind Bitcoin, it must be said that what Ethereum has been doing has been working exceedingly well. The transition to PoS presents both a new opportunity and a challenge to long-term value accrual to the ETH token.

But in a world where monetary networks tend to converge on a single medium, there is a reason that utility commodities such as oil, copper and silver have not held up over time as a store of value relative to the scarcest asset, gold.

The biggest prize to be won, and most value to be accrued, for any free market economic good is to be adopted as money, and in this, over time, there can only be one.

Cost to Run a Node

Contrary to popular belief, PoS naturally promotes decentralization more than PoW. Larger PoW miners receive a clear benefit from economies of scale, which drives centralization. Scale is less relevant for PoS, as the cost of setting up a node is vastly lower than a PoW rig. Furthermore, there is no real benefit in having access to large-scale electricity providers, as the electricity required for PoS is 99%+ lower. Economies of scale are very important for PoW, but not for PoS.

The cost of setting up an Ethereum node relative to a PoW mining rig, while both important for decentralization, is comparing apples to oranges as they do perform different functions. While I agree scale is important in bitcoin mining, as I’ll examine below, sub-scale miners pool resources to achieve economic scale. On the other hand, I would argue scale is essential in running an ETH full-node and doing so is necessarily a centralized function with no capacity to decentralize, unlike a bitcoin mining pool which consists of a number of smaller bitcoin mining operations that have the ability to split off and operate independently if warranted, even if their economics would change meaningfully.

“Running a node” is running the respective blockchain’s software locally to verify the entire history of the state of the ledger, audit the supply of the native token, and verify the network’s consensus rules are being followed. This is different than being a miner (PoW BTC) or validator (PoS ETH), which, respectively, are the entities that process new transactions and propose new blocks to the added to the blockchain, which are then accepted or rejected by node operators.

When discussing the cost of setting a Ethereum node it must be acknowledged there are various levels of nodes: full node, top-level node, single-shard node, light node. Indeed, much of this complexity was introduced during the merge in an attempt to make it more accessible for individuals to run a single-shard node or a light node, to increase decentralization.

But running a full node takes terabytes of storage space and commercial-grade bandwidth, and those are the only nodes that store the entire history of the Ethereum blockchain. Any other node is only storing data for a small portion of the blockchain, and is reliant upon those able to run a full-node for the integrity of the entire network.

On Ethereum, unless you are running a full-node, you must trust and you cannot verify, and to reiterate, the computational resources required to run a full-node (terabytes of storage and massive bandwidth) are not available to all but sizable commercial entities.

On Bitcoin, you can run a full-node with a $200 laptop computer and a standard internet connection as only about 350 gigabytes of storage space and 500 megabytes of bandwidth per day are required. Don’t trust, verify.

On the miner/validator front, the cost to be an ETH validator starts at $64,000 at current market prices, since it requires 32 staked ETH to be a validator.

In contrast, you can spend anywhere from $329 on Amazon Prime to $2,860 for a top of the line, industrial grade Bitcoin mining rig.

It is unequivocally cheaper to run a bitcoin full-node than an ethereum full-node, and likewise to own and operate a bitcoin mining rig than an ethereum validator.

ETH Staking Pool and BTC Mining Pool Concentration

We can end here with a warranted discussion of the similar, but I think ultimately different, challenges both protocols face in terms of the centralization of staking pools (ETH) and mining pools (BTC).

~540,000 unique ETH validators exist today and the top 5 holders only control 2.33% of the stake (excluding smart contract deposits). This level of decentralization and diversity separates ETH from all other PoS L1’s. Furthermore, this compares to BTC favorably as the top 5 mining pools today control ~70% of the hashrate. While some critics will point out that liquid staking providers control an overwhelming portion of Ethereum’s stake, we believe these concerns are overblown. Additionally, we expect these concerns to be addressed by the liquid staking protocols and expect more checks to be put in place to further protect against these concerns.

In summary, for all the reasons outlined above, we believe PoS is a fundamentally better consensus mechanism for a crypto SoV than PoW. From a token perspective, as the largest PoS token with the most credible claim to decentralization, we believe ETH is the best candidate that exists today.

When Hal mentions that critics will point out that liquid staking providers control an overwhelming portion of staked ETH, this is what he’s referring to:

The concern is that if a few, or as little as two, of these entities teamed up and wanted to, for whatever reason, they could combined hold >50% of the stake (assuming no additional ETH was staked, which is an important point as we’ll see) and in doing so could attempt to execute a 51% attack.

Another concern here is censorship. In the wake of the merge to PoS and OFAC’s sanctions on Tornado Cash, the level of OFAC-compliant blocks processed by validators rose as high as 79%. This means 79% of all validators were complying with U.S. regulatory standards and censoring transactions. Parties attempting to transact on Ethereum in a non-OFAC compliant way would still be able to, but they’d have to wait longer to get their transactions processed. As long as, say, >1% of the validators are not operating in an OFAC-compliant manner, then you might say the chain is still censorship-resistant as that 1% is eventually able to process blocks with the transactions that the other 99% refuses to include in their blocks. But it’s not really open, accessible, permissionless or fair. The “bad guys” as determined by a U.S. regulatory body have to wait in line for their transactions to be processed, and also ultimately need validator permission to use the chain. Anyone can become their own validator, but as mentioned you need to stake 32 ETH to do so (~$64,000), making it out of the reach of most individuals globally and hence, why you see the consolidation into a few centralized stakers in the pie chart above.

The motivation for individuals or smaller entities to pool their ETH in these liquid staking pools is/was thus primarily two-fold: 1) they do not have the financial and/or technical resources to set-up their own validator and stake 32 ETH and/or 2) they preferred to earn staking rewards on their ETH while remaining liquid through what are called liquid staking derivative tokens issued by liquid staking pools. The latter was more of a concern pre-Shapella upgrade, since any ETH staked was locked and illiquid until that upgrade was shipped.

The key point here though is that it is only ETH stakers who 1) have the technical resources to set up their own validator but 2) do not have the financial resources to acquire 32 ETH are truly “pooling” their assets in the traditional sense. By that I mean combining resources with others in order to get access to something you couldn’t on an individual level. Think of a real-estate investment trust, which allows retail investors to own a stake (there’s that word again, hmmm) in trophy real estate assets without having the money to buy the whole thing, for example. ETH holders who are using ETH staking pools in part because either they don’t have the ability to run a validator or they want liquidity while earning staking rewards, are actually paying for a service, and they are giving up a portion of their staking rewards for the service. For example, Lido takes 10%, and Coinbase takes 25%.

The Bitcoin version of what I’ll call the “centralized validators” problem is mining pools.

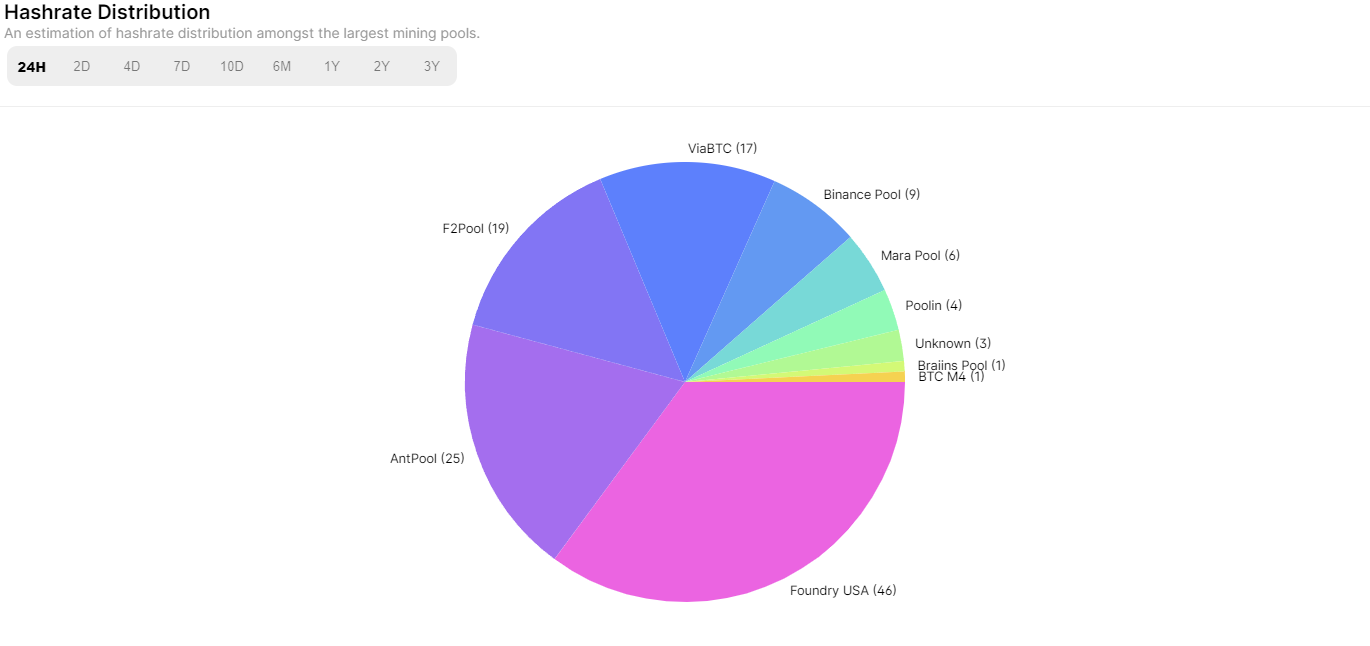

This chart shows that, much like the ETH staking pools, the two largest BTC mining pools have committed >50% of the hashrate to the Bitcoin network (past 24 hours as I write this). If they wanted to, they could similarly team up to attempt a 51% attack.

Much like a staking pool, a mining pool represents a bunch of individuals and smaller entities pooling their resources together for mutual benefit, but the nature of the “pooling” relationship is different. Bitcoin mining is just a brute force computing competition to solve a difficult math problem, and winning the competition, and thus the block reward, is like winning the lottery. It’s a function of how many tickets you buy (how much computing power, i.e. hashrate you’re dedicating to solving the math problem) and pure chance (this is in conrast to ETH staking, where an algorithm ensures every staking as little as the minimum 32 ETH get’s their pro-rata share of staking rewards). As such, while a small bitcoin miner can expect to win their fair share of the block rewards over the long, long run, it is likely that operating alone they would go long periods in between winning, all while sustaining the cost to operate. For a sub-scale bitcoin miner, evenue is extremely lumpy and unpredictable in timing while costs are constant and predictable.

To solve for this problem, bitcoin miners ranging from individuals to publicly traded enterprises pool their resources into a mining pool. They all contribute their hashrate to the pool, and whenever one of them gets lucky and wins the block reward, the reward is split among all of them in proportion to their contributions. This smooths out revenue for all of them in comparison to operating on their own.

So, bitcoin miners are pooling their resources in the traditional sense: combining their resources to get access to something they could not individually, in this case, a more predictable stream of block rewards over time. This is not to say some bitcoin miners, especially individuals, are not also paying for goods and services, such as renting mining rigs or shelf space at a mining facility, but these costs are typically discrete and accounted for separately (see note at bottom).

Many of these bitcoin mining operations, accounting for most of the hashrate, likely have everything in place to flip the switch and operate independently if warranted, and/or could easily split up to form their own smaller but independent mining pools. That is to say, there is no technical or scale barrier to them doing so, just increased economic risk and uncertainty. On the other hand, I think it is overwhlemingly likely that a majority of Lido or Coinbase staking clients could not flip the switch and begin operating their own validators. If they have the scale and technical chops to do it, it is likely they already would have spun up their own operation as opposed to pay the 10-25% service fee.

In diving into the specifics of the two largest bitcoin mining pools — Foundry USA and Antpool — it starts to seem a bit like these pools might be the private market beginnings of nation-state level hashforces.

Foundry USA is owned and operated by the eponymous Foundry, part of Digital Currency Group’s crypto empire. By the end of 2020, Foundry helped procure half of all the Bitcoin mining hardware delivered to North America.

Antpool is owned and operated by Bitmain, the vertically integrated bitcoin mining hardware manufacture know for its Antminer series. Despite the ostensible crypto mining ban instituted in China in May 2021, both Bitmain and subsidiary Antpool have headquarter’s in China.

One might speculate that Foundry USA and Antpool teaming up to 51% attack the netwrok, then, is about as likely as the U.S. and China teaming up to set a new world order. On the other hand, 6 out of 9 ETH staking pool operators listed above are domiciled in the U.S. (as well as others in Europe), including the top two known staking pools operated by Lido and Coinbase, and are know to be complying with U.S. regulations on censorship.

But, admittedly, much of would they/won’t they/could they team up is just speculation.

Here is the key point:

If any one entity or coordinated consortium manages to obtain 51% of the hashrate on the bitcoin network, they would need to maintain it over time to execute a 51% attack and there is nothing stopping the other 49% from increasing their hashrate to wrest a majority of the hashrate back away from the 51% attackers.

Bitcoin security is unbounded and positive-sum.

It is also worth mentioning here that any build-up of 51% of the hashrate would likely be visible and suspected by the competition, giving them time to step-up production of their own hashrate as a deterrent. This is akin to a modern day arms race, and the dynamic that spurs ideas like hashforce and hashwars into the theory of how this might all play out.

In stark contrast, if any one entity or coordinated consortium manages to obtain 51% of the supply of ETH, i.e. “stake” in the ownership over the network, then there is nothing the other 49% can do to wrest control of the network back from the 51% attackers.

Ethereum security is bounded and zero-sum.

Ethereum has many, many competing Layer-1 PoS blockchains that compete on dimensions of speed, security, decentralization.

Bitcoin has no competition as a decentralized, apolitical, absolutely scarce, credibly neutral cryptoasset secured by physical force.

It is the only decentralized money, and this is why decentralized money matters.

Note: Foundry notified clients April 6, 2023 that it was going to stop providing its services for free, according to Bloomberg. The changes were scheduled to go into effect between April 19-22, at which time clients would be separated into tiers based on the previous quarter’s average hashrate contributed to the pool, and charged a service fee based on tier.

Foundry’s parent company, Digital Currency Group, is currently under acute financial stress and as a result a major shake-up in the U.S. bitcoin and crypto landscape could be underway, including the fate of Foundry and Foundry USA. It remains to be seen how it will all play out, but possible outcomes include a deconsolidation of hashpower away from the Foundry USA mining pool as scaled operators opt not to pay the newly instituted fee for inclusion or split-off in preparation for the uncertainty of potential asset sales and bankruptcy proceedings at DCG.

Loved this. Thoughts / comments:

1. The discussions of 51% attacks seem overblown because it's wrong-way risk for the attacker. Any 51% attack would delegitimize the currency (unless the currency has reached a point of adoption that is far away from where we are today). So, to your point, a 51% attack would probably need to be done in conjunction with a short, but who is your counterparty in the short? The logistics of getting a payout seem tricky to pull off.

2. You talk about Eth gas fees leading to centralization. If I understand right, your argument is basically that lower-dollar accounts have a higher velocity ... sort of analogous to how sales taxes are regressive because poorer consumers have higher marginal propensity to consume, whereas rich people can invest their money and pay lower taxes on capital gains (ignoring income taxes in this analogy) Even if we take this argument at face value, doesn't Bitcoin have same dynamic? Fees are paid on a per-transaction basis (increasingly so as Bitcoin asymptotically approaches its hard cap), so the accounts that transact more frequently get eaten away. (Yes, the issuance of new Bitcoins is dilutive for everyone in proportion to current ownership, but more on that below.)

3. Your discussion of what happens when Bitcoin rewards go down is really interesting, including your note that fees are not static but instead a dynamic marketplace. If I am understanding correctly, issuing new Bitcoin is akin to inflation, so all users are paying "hidden gas fees" in the same way inflation is a "hidden tax" on the middle class. Similarly, as Bitcoin new issuance approaches zero, the "hidden gas fees" go away and will likely get replaced with higher real gas fees: this is akin to shifting the tax burden away from fiat inflation to higher sales taxes.

4. You write: "No physical input is required to “earn” ETH, whereas it is required to earn BTC." I mean, if you accept the argument that those who have fiat currency have earned it by adding value for others in society, then converting fiat to ETH is actually arguably a better required input cost than solving useless math problems, no?

5. The thing that blows my mind about Bitcoin setup (that I had not realized until reading this article) goes back to Bretton Woods. When Bretton Woods was being negotiated, the final compromise reached was GOLD>>USD>>FX, whereby FX was convertible for USD, which in turn was convertible for gold. Keynes proposed the Clearing Union, with all currencies exchangeable to a centralized currency that was in turn exchangeable for an underlying commodity basket. In practice, when the US left the gold standard, the dollar has served as exchangeable for oil (i.e. energy) at a not-too-quickly-depreciating price. With Bitcoin using energy as an input, THAT IS EXACTLY WHAT BITCOIN IS. The price of mining a marginal Bitcoin is reflective of the cost of energy that goes into mining it, and thus it will be difficult for Bitcoin not to move with the cost of energy ... and when we talk about inflation, we are really talking about the cost of energy. (This is a loose/new thought so feel free to poke holes ... it's an analogy but not sure it's airtight.)

_______________________________________________________________

I completely understand and agree that RELATIVE to ethereum, bitcoin is a much better candidate to become digital gold (notably the credible neutrality and distribution fairness). However I still see two reasons that will make it hard for Bitcoin ever to become digital gold:

1. The public nature of the ledger makes means that certain coins can become "dirty coins" (like Mt Gox) which risks reducing the fungibility of asset and making certain coins illegal to own in a way that would be much harder to conceive for gold. The best bull case here is that Bitcoin becomes a currency for money laundering or for trade used by nations not friendly to the US.

2. You discussed the fairness of the initial distribution as allocation to miners. Yes, this may be fair from a moral perspective and a credible neutrality perspective. From a practical perspective, however, an idealized digital gold would have a distribution that mirrors the distribution of current gold reserves. This would have meant a "drop" to central banks in proportion to how much gold they currently have. Similar to the "dirty coins" note above, since central banks do not currently own Bitcoin, the success of Bitcoin will likely involve going to war with central banks rather than operating through their existing infrastructure (like gold did for so many years), which will likely make its adoption much more difficult.